The Return of the Prairie Populists

In 1892, the People’s Party gathered in Omaha to declare within their first platform that “we have witnessed for more than a quarter of a century the struggles of the two great political parties for power and plunder, while grievous wrongs have been inflicted upon the suffering.” Prairie progressives seem poised to reclaim that platform.

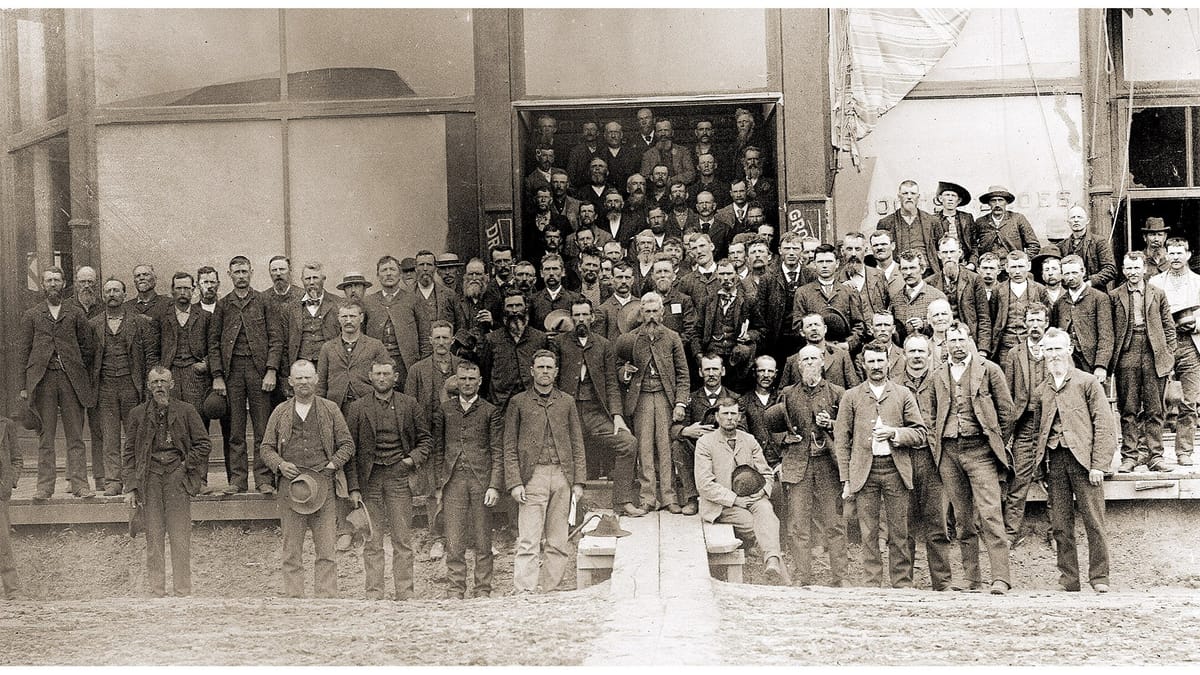

The northern American plains are undergoing something of a progressive-populist resurgence, epitomized by Dan Osborn in Nebraska and Tim Walz in South Dakota. While the faux-populism and American First nativism of Donald Trump continues to capture voters in the deeply red states of the northern plains, there's a long history of prairie progressivism that remains embedded in the region's political culture. This is, after all, the same region that produced Luna Kellie and George Norris in Nebraska, Bob La Follette in Wisconsin, Henry Loucks in South Dakota, Arthur C. Townley in North Dakota, and widespread Alliance and Populist movements in the early twentieth century. These political movements fused labor-agrarian-populist sentiments that led to things like North Dakota's state ownership of banks, rail lines, and grain mills, as well as long-standing alliances between farmers and laborers.

Nor are these histories isolated to the turn of the century. On November 1, 1983, "Solidarity Day" led farmers to provide free breakfasts at a North Minneapolis YMCA, where United Auto Workers leader Bob Killeen and Minnesota civil rights activist Spike Moss spoke before an at-capacity venue. Farmers and activists then drove the two hours north to Minnesota's Iron Range, where 65% of miners faced unemployment. Minnesota also gave us Paul Wellstone, the college professor-turned-state senator whose rural campaigning style on progressive policies led him to win his underdog race in 1990 (in the wake of the senator's death in a plane crash in 2002, aides and supporters started Camp Wellstone to work with and train politicians, activists, and operatives. Tim Walz was an attendee.)

Throughout the early 2000s the northern plains steadily became redder as Democrats embraced neoliberalism and Republicans pursued cultural politics: David Minge lost his seat in 2000, Tom Daschle in 2004, and Republicans flipped seats across Iowa, Nebraska, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin.

Flipped Northern Plains Congressional Seats, 2000-2024

David Minge (D) | Mark Kennedy (R) | MN | 2000 | House |

Tom Daschle (D) | John Thune (R) | SD | 2004 | Senate |

Bob Kerrey (D) | Deb Fischer (R) | NE | 2012 | Senate |

Heidi Heitkamp (D) | Kevin Cramer (R) | ND | 2018 | Senate |

Jason Lewis (R) | Angie Craig (D) | MN | 2018 | House |

Erik Paulsen (R) | Dean Phillips (D) | MN | 2018 | House |

Kevin Yoder (R) | Sharice Davids (D) | KS | 2018 | House |

Rod Blum (R) | Abby Finkenauer (D) | IA | 2018 | House |

David Young (R) | Cindy Axne (D) | IA | 2018 | House |

Dan Feehan (D) | Jim Hagdorn (R) | MN | 2018 | House |

But there's a sense in which populist-progressives are regaining ground. For Walz, winning over southern Minnesota, a fairly conservative place, is in and of itself remarkable and a testament to learning from Wellstone's rural campaigning methods. But he's also supported "fair trade" and family farmers, and has famously expanded free lunch programs, signed climate-friendly pledges, and codified the right to abortion in Minnesota, supported labor rights, created a public option for Minnesota healthcare, and signed a $2.6 billion package in 2023 for funding construction jobs.

Nebraska is also feeling the pull of progressive politics. The unlikely candidacy of Dan Osborn, an independent candidate and union leader known for leading a strike at Kellogg's Omaha plant in 2021, is very close to unseating two-term Republican senator Deb Fischer. Osborn has seemingly filled a void between neoliberal Democrats and left-leaning grassroots momentum once filled by producer-populists, union allies, and anti-monopolists. Osborn has situated himself within this blue-collar populist vein—a Navy veteran, father of three, and fired for his union organizing and retrained to be a steamfitter—as he strikes back at both Fischer and the Democratic Party's "corporate agenda." His criticisms are what I'd consider purely midwestern: appealing to Nebraskans who strongly dislike outside influence, whether that's an unaccountable federal bureaucracy or corporate multinationals. His message is clear: to rebuild rural communities, we have to support workers. And by denying support from the state's Democratic Party, he's situating his argument that the Democratic Party is so weakened in rural places that they are not any use in the race.

It's an interesting contrast to Minnesota, where the DFL has regained governing power, while Democrats in Nebraska struggle to become more than just token opposition. Despite that, there are strong left-leaning political traditions on the American plains that Walz and Osborn tapped in to and which points towards a way for Democrats to regain ground. We'll see how this plays out in other plains states on Tuesday.