How Markets Replaced What Took Millennia to Build

I suppose we need not go mourning the buffaloes. In the nature of things they had to give place to better cattle.

—John Muir

The population collapse of plains bison, that symbolically most American mammal (Bison bison bison), is among the most well-known stories of our animal past. For thousands of years millions of these ancient animals, originating from Asia across the Bering land bridge, followed migration paths across the Great Plains in search of grass, water, shelter, and seasonal weather. For over 2,000 human generations millions of bison ranged over a great swath of North America, as far north as Alaska to the Gulf of Mexico.

Commercial hunting and slaughter brought them near extinction in just thirty years.

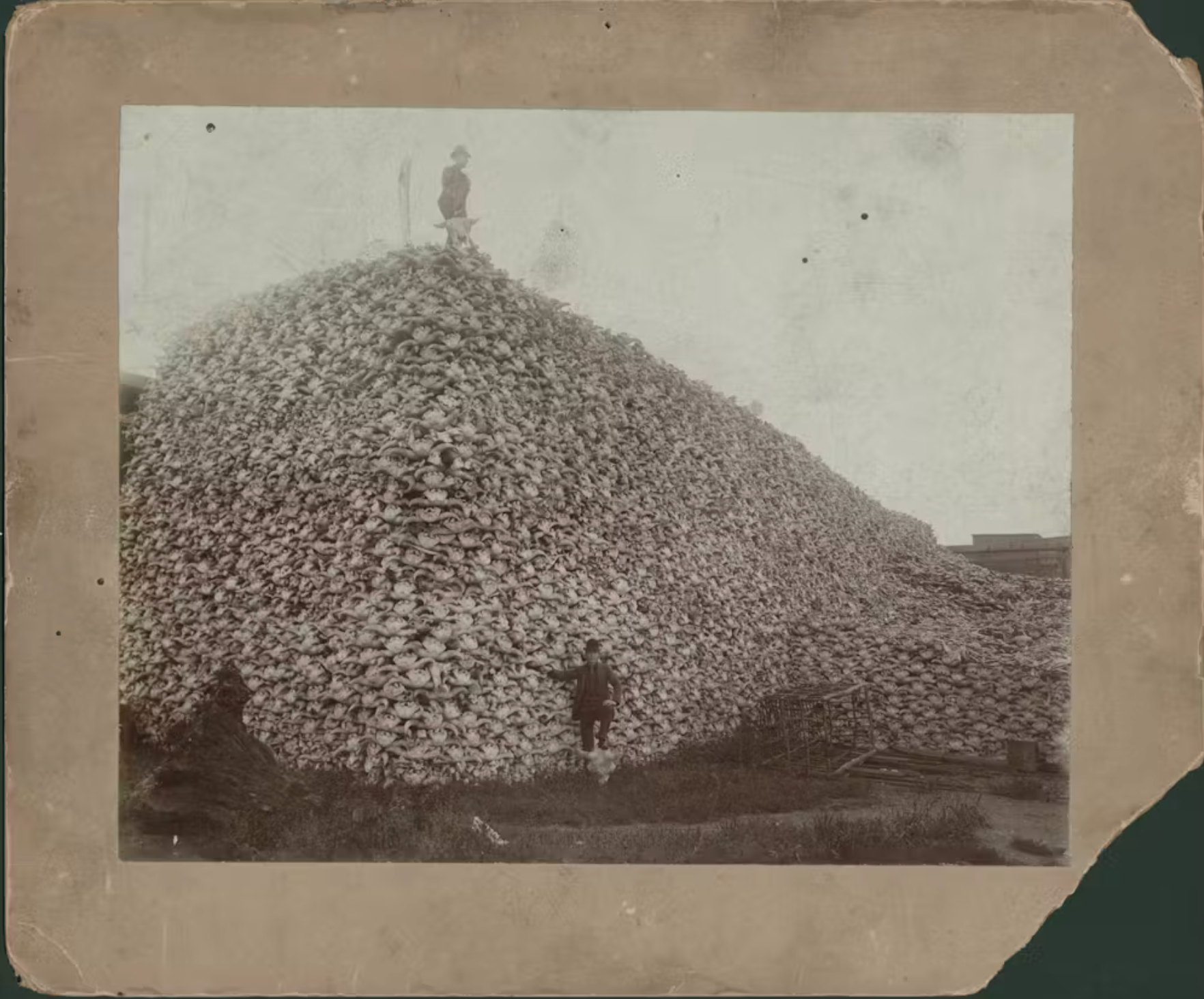

Many readers are likely familiar with the famous grisly photograph of the mound of bison skulls, taken outside the Michigan Carbon Works in Rougeville in 1892. Between 1860 and the year the photo was taken, the largest killing spree of American animals occurred (and not just bison, but wolves, coyotes, and untold millions of others through incidental poisoning). An estimated 30-60 million bison roamed the country in 1800. By 1889, William Hornaday's systematic census of bison populations counted fewer than 500 remaining. Bison populations could not overcome the market pressures placed on them.

Bison populations take time to grow. With relatively late reproductive maturity (typically around 6 years) and long gestation periods (285 days), the enormous pressure placed upon the herds by American settlers meant that, biologically, they could never have replaced their populations as quickly as they were being killed.

As a keystone species, bison greatly shape ecosystems. Their grazing, migration, and wallowing created new habitats for animals and plants. Bison feed on grasses, sedge, forbs, and woody plants, creating a more complex ecosystem than monocultures that are often fed to cattle. Their shaggy coats allowed seeds to travel and disperse, and they shed their coats in spring by rubbing against small trees. This would often kill the tree, stopping forests from moving onto the plains and encouraging other thriving habitats. Like cattle, their hooves churn and aerate soil as they travel. Unlike cattle, bison ranged over farther distances for water and food. Like farmers using modern cultivation equipment, this loosened and aerated soil provided a receptive environment for new seeds. Bison feces likewise provided environments for dispersing seeds, bacteria, and insects to recycle nutrients into the soil, and, as buffalo manure supported bug populations, this, in turn, supported bird populations.

Privatizing the Great Plains radically altered this ecosystem. As Dan Flores notes, with new human settlement east and west of the plains bison lost a place of refuge from droughts that they'd used for millennia. The market for bison—sometimes for hides, sometimes for skulls, very rarely for meat, and often for slaughter that simply left bison carcasses rotting in the heat—rapidly destroyed their populations in a way that's hard to wrap your mind around. Nineteenth-century Americans could not conceive that humans could be responsible for such destruction, instead suggesting alternatives other than themselves to explain the dwindling herds—an echo of the denials we hear now about climate change.

The demise of bison populations directly followed two key developments: the expansion of railroads, and the rise of cattle populations.

The cows came before the rail. Fifteenth century Spanish settlers introduced cattle husbandry to the Southwest. When Spain abandoned its northern mission settlements locals rounded up mostrencos, mesteños, orejanos, and cimarrón cattle across East Texas and driving them to the New Spain port of New Orleans. Cattle businesses were thriving when the borders of the United States swept over the Southwest. By 1865, Texas alone counted 5 million longhorns. Cattle drives across the Plains typically numbered between 500 to 10,000 head. By the 1880s—as bison numbers hovered around 500—an estimated 7.5 million cattle grazed the plains.

The new bovines drastically impacted the ecosystem. Like bison, cattle feces provided a similar environment for seeds, bugs, and bacteria, but their confinement tended to churn and compact the ground making it harder for grasses to reseed. Even on open ranges, the trampling and overgrazing of grasses overburdened native plants and allowed European weeds to proliferate, made worse as climatic conditions in the nineteenth century varied the carrying capacity of grasses. Cattle, in other words, did not follow the same migratory grazing patterns of bison. Nor did cattle benefit from anthropogenic fires, used by Indigenous peoples to promote healthy grasses and suppress junipers, scrub, and shrubs. This new cattlescape was fed by the same market system that led to the collapse of bison populations: the grasslands could never hope to keep up with the extreme increase of centralized animal herds that fed beef consumers and profits.

Technology helped push these changes further. Railroads had a close relationship to the cattle kingdoms, first as avenues for people, goods, and livestock to travel faster into the American West and, then, as avenues for market commodities for eastern consumers. As rail lines expanded across the Midwest and West, cattle drives became less useful. Instead, cattle (or, after refrigeration, their carcasses) could be transported by rail to stockyards in Chicago or Omaha or St. Louis then to markets along the east coast.

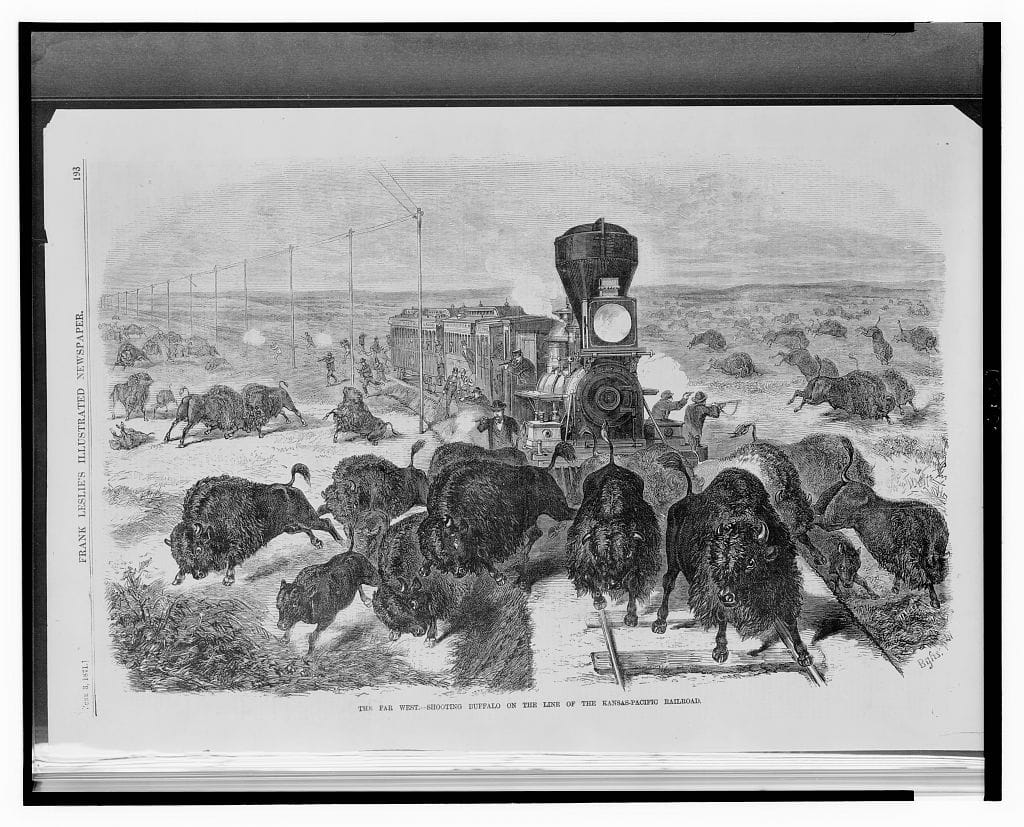

The railroads themselves saw bison as an impediment. The animals interfered with their expansion plans, slowing construction or crossing tracks in front of locomotives. Hunters killed bison for all manner of reasons: to feed railroad workers, to chase the animal from construction areas, or, pathetically, for entertainment from their railcars. Harpers Weekly described a typical unsporting scene:

Nearly every railroad train which leaves or arrives at Fort Hays on the Kansas Pacific Railroad has its race with these herds of buffalo; and a most interesting and exciting scene is the result. The train is "slowed" to a rate of speed about equal to that of the herd; the passengers get out fire-arms which are provided for the defense of the train against the Indians, and open from the windows and platforms of the cars a fire that resembles a brisk skirmish. Frequently a young bull will turn at bay for a moment. His exhibition of courage is generally his death-warrant, for the whole fire of the train is turned upon him, either killing him or some member of the herd in his immediate vicinity.

Bison recovery efforts in the twentieth century have helped restore some of their populations. The bison has gone from a source of food and clothing, to a market and a sport, to something we conserve. Thirty years of market pressures between 1850 and 1880 destroyed what had existed for millennia, fundamentally changing the Great Plains in ways less sustainable and biodiverse. This effort proceeded from the idea that this shift was "progress"—supplanting native flora, fauna, and people from the Plains with new animals, new cultures, and white people.

Many nineteenth century Americans could not imagine maintaining bison herds alongside this shift, just as we today struggle to imagine agriculture, technology, development, and industrialization that works with the natural world rather than against it. The same market logic that drove bison to near extinction now struggles to account for carbon sequestration, soil health, and climate resilience—something restored prairies, for example, can provide. But the health of the prairies, the health of ecosystems broadly, requires working with ecosystems rather than replacing them.

Readings

In addition to the links above, I would encourage checking out the following that I also consulted. A shoutout specifically to Dan Flores for prompting me to think about this.